The new company is officially founded and has got a name: DataMarket. You’ll have to stay tuned to hear about what we actually do, but the name provides a hint 😉

The new company is officially founded and has got a name: DataMarket. You’ll have to stay tuned to hear about what we actually do, but the name provides a hint 😉

In the last couple of weeks I’ve spent quite some time, thinking about the big picture in terms of DataMarket’s technical setup, and it’s led me to investigate an old favorite subject, namely that of cloud computing.

Cloud computing perfectly fits DataMarket’s strategy in focusing on the technical and business vision in-house while outsourcing everything else. In other words, focus on the things that will give us competitive advantage, but leave everything else to those that best know how. Setting up and managing hardware and operating systems is surely not what we’ll be best at, so that task is best left to someone else.

This could be accomplished simply by using a typical hosting or collocation service, but cloud computing gives us one important extra benefit. It allows us to scale to meet the wild success we’re expecting, yet be economic if things grow in a somewhat milder manner.

That said, cloud computing will no doubt play a big role in DataMarket’s setup. But there are different flavors of “the cloud”. The next question is therefore – which flavor is right for this purpose?

I’ve been fortunate enough this year to hang out with people that are involved in two of the major cloud computing efforts out there: Force.com and Amazon Web Services (AWS). Additionally I’ve investigated Google AppEngine to some extent, and I saw a great presentation of Sun’s Network.com at Web 2.0 Expo.

These efforts can roughly be put in two categories:

- Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS): AWS and Network.com

- Platform as a Service (PaaS): Google AppEngine and Force.com

IaaS puts at your disposal the sheer power of thousands of servers that you can deploy, configure and set to crunch on whatever you throw at them. Granted, the two efforts mentioned above are quite different beasts and not really interchangeable for all tasks. Network.com is geared towards big calculation efforts, such as rendering of 3D movies or simulating nuclear chain reactions, whereas AWS is suitable for pretty much anything, but surely geared towards running web applications or web services of some sort.

PaaS gives you a more restricted set of tools to work with. They’ve selected the technologies you’re able to run and given you libraries to access underlying infrastructure assets. In the case of Force.com, your programming language is “Almost Java”, i.e. Java with proprietary limitations to what you’re able to do, but you also get a powerful API that allows you to make use of data and services available on Salesforce.com. AppEngine uses Python and allows you to run almost any Python library. In a similar fashion to Force.com, AppEngine gives you API access to many of Google’s great technological assets, such as the Datastore and the User service.

In short, the PaaS approach gives you less control over the technologies and details of how your application works, while it gives you things like scalability and data redundancy “for free”. The IaaS approach gives you a lot more control, but you have to think about lower levels of technical implementation than on PaaS. Example: On AWS you make an API call to fire up a new server instance and tell it what to do – on AppEngine, you don’t even know how many server instances you’re running – just that the platform will scale to make sure there is enough to meet your requirements.

So, which flavor is the right one?

The thinking behind PaaS is the right one. It takes care of more of the technical details and leaves the developers to do what they’re best at – develop the software. However, there is a big catch. If you decide to go with one of these platforms, you’re pretty much stuck there forever. There is no (remotely simple) way to take your application off Force.com or AppEngine and start running it on another cloud or hosting service. You might find this ok, but what if the company you’re betting your future on becomes evil? or changes their business strategy? or doesn’t live up to your expectations? or want’s to acquire you? or – worse yet – doesn’t want someone else to acquire you?

You don’t really have an alternative – and you’re betting your life’s work on this thing.

Sure. If I was writing a SalesForce application or something with a deep SalesForce integration, I’d go with Force.com. Likewise, if I was writing a pure web-only application, let alone if it had some connections with – say – Google Docs or Google Search, I’d be very tempted to use AppEngine. But neither is the case.

So the plan for DataMarket is to write an application that is ready to go on AWS (or another cloud computing service offering similar flexibility), but try as much as possible to keep independent of their setup. Not that I expect that I’ll have any reason to leave, but there is always the black swan, and when it appears you better have a plan. This line of thinking even makes me skeptical of utilizing their – otherwise promising – SimpleDB, unless someone comes up with an abstraction layer that will allow SimpleDB queries to be run against a traditional RDBMS or other data storage solutions that can be set up outside the Amazon cloud.

Yesterday, I raised this issue to Simone Brunozzi, AWS’ Evangelist for Europe. His – very political – answer was that this was a much requested feature and they “tended to implement those”, without giving any details or promises. I’ll be keeping an eye out for that one…

So to sum up. When I’ve been preaching the merits of Software as a Service (think SalesForce or Google Docs) in the past, people have raised similar questions about trusting a 3rd party for their critical data or business services. To sooth them, I’ve used banks as an analogy: A 150 years ago everybody knew that the best place to keep their money was under their mattress – or even better – in their personal safe. Gradually we learned that actually the money was safer in institutions that specialized in storing money, namely banks. And what was more – they paid you interest. The same is happening now with data. Until recently, everybody knew that the best place for their data was on their own equipment in the cleaning closet next to the CEO’s office. But now we have SaaS companies that specialize in storing our data, and they even pay interest in the form of valuable services that they provide on top of it.

So, your money is better of in the bank than under your mattress and your data is better of at the SaaS than on your own equipment. Importantly however, at the bank you have to trust that your money is always available for withdrawal at your convenience and in the same way, your data must be “available for withdrawal” at the SaaS provider – meaning that you can download it and use it in a meaningful way outside the service it was created on. That’s why data portability is such an important issue.

So the verdict on the most suitable cloud service for DataMarket: My application is best of at AWS as long as it’s written in a way that I can “withdraw” it and set it up elsewhere. Using AppEngine or Force.com would be more like depositing my money to a bank that promptly changes all your money to a currency that nobody else accepts.

I doubt that such a bank would do good as a business!

Við erum, nokkrir félagar, að hleypa af stokkunum í dag nýju vefsvæði: opingogn.net

Við erum, nokkrir félagar, að hleypa af stokkunum í dag nýju vefsvæði: opingogn.net

Þann 1. apríl síðastliðinn stofnaði ég banka. Þetta er alþjóðlegt fjármálafyrirtæki og af þeim sökum var höfuðstóllinn auðvitað í erlendri mynt: 1.000 evrur í fimm brakandi 200 evra seðlum.

Þann 1. apríl síðastliðinn stofnaði ég banka. Þetta er alþjóðlegt fjármálafyrirtæki og af þeim sökum var höfuðstóllinn auðvitað í erlendri mynt: 1.000 evrur í fimm brakandi 200 evra seðlum.

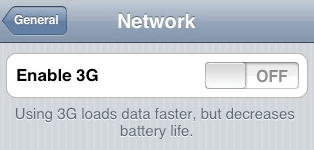

The rumours are getting ever louder. The new version of iPhone is coming out

The rumours are getting ever louder. The new version of iPhone is coming out  I’ve just had a very interesting experience that sheds light on some important issues regarding copyright, online data and crowdsourced media such as wikis. I thought I’d share the story to spark a debate on these issues.

I’ve just had a very interesting experience that sheds light on some important issues regarding copyright, online data and crowdsourced media such as wikis. I thought I’d share the story to spark a debate on these issues.